1966-1977 American Antartic Mountaineering Expedition, Antarctica

The pages of this journal were transcribed essentially verbatim from what I wrote in ball-point pen in a 5”x8” lined record book, much of which written while sitting up in a small mountain tent at the end of a long day. Regardless of the circumstances, and for whatever reason, I made an effort to write in full sentences and use correct spelling and even punctuation. I wrote on the right-hand page until the book was full near the end of the trip, at which time I turned it upside down to start back on the facing page. After the fact I scotch-taped a number of small photos where they matched the diary entry du jour.

In typing the diary I decided to make some small edits to correct spelling errors (e.g. nunataks vs. nunatacks) and inconsistencies (Charley vs. Charlie Hollister), but otherwise the typed version is the same as the original except that I have included several more photos and added a number of explanatory comments as footnotes—these in the event that this should fall into the hands of a reader innocent of foreknowledge of mountaineering, Antarctica, or me.

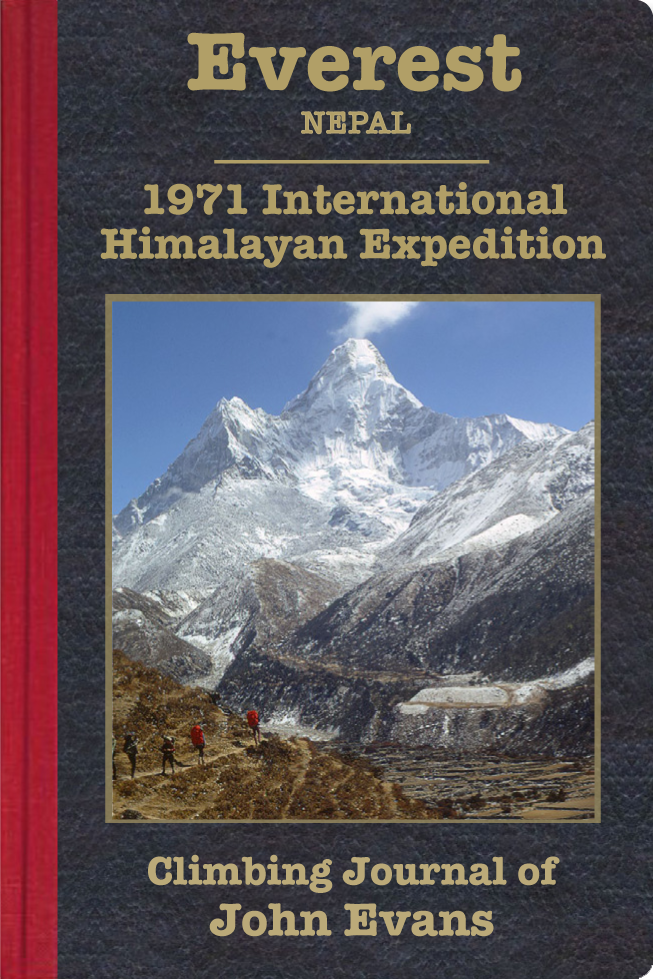

This diary is nothing more than my own impressions and by no means should be viewed as the whole story or even a balanced story of the expedition. The latter can be found in the June, 1967 issue of National Geographic Magazine, which makes much of the fact that this was the historic first ascent of the last high point of the seven continents–the 6th continental summit being Asia’s Mt. Everest.

Historic significance or no, it is of interest that at the time Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached Everest’s summit in May of 1953 the Vinson Massif was completely unknown. The discovery of Vinson—and essentially the entire Sentinel Range had to wait until December of 1957, when it was seen virtually simultaneously by an overland traverse party from the University of Wisconsin and a US Navy airplane flying reconnaissance. Photos taken by a later US Navy reconnaissance flight were published in the internationally-read Swiss publication, The Mountain World (1960-61); this drew the instant attention of the world-wide mountaineering community to the existence of significant mountaineering possibilities in the Antarctic interior, and the attractive possibility of making the first ascent of the last continental summit.

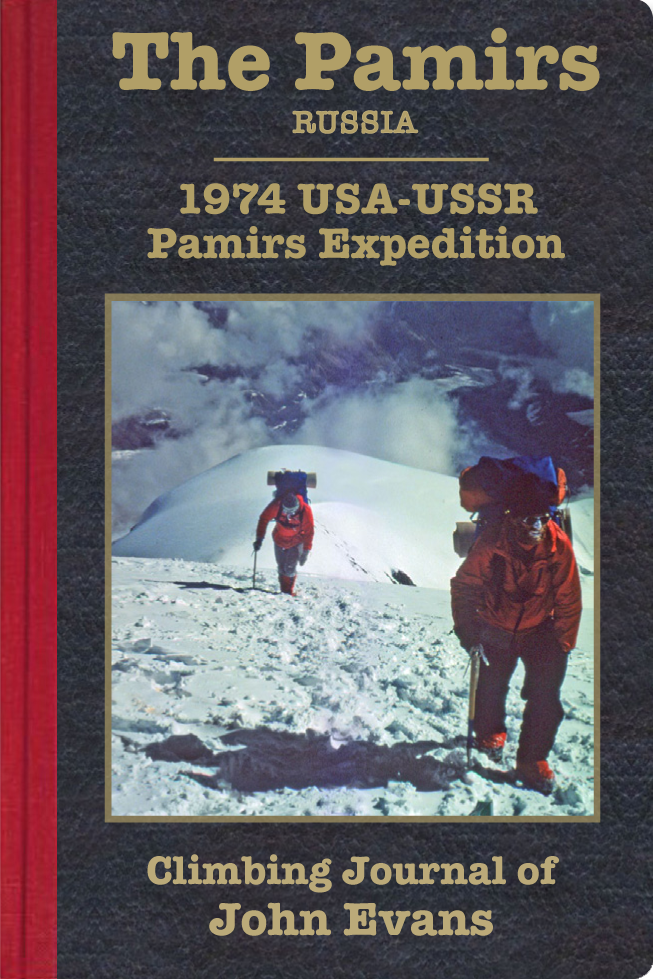

Coming as it did while the US-USSR space race was going full-tilt, significant nationalistic interest developed in the US to foster an unprecedented (and not-to-be-repeated) support collaboration including the National Geographic Society and such improbable governmental entities as the U.S. Departments of State and Defense and the National Science Foundation, each of which had an implied or overt interest in seeing to it that the first flag to wave on this final continental summit would be that of the United States.

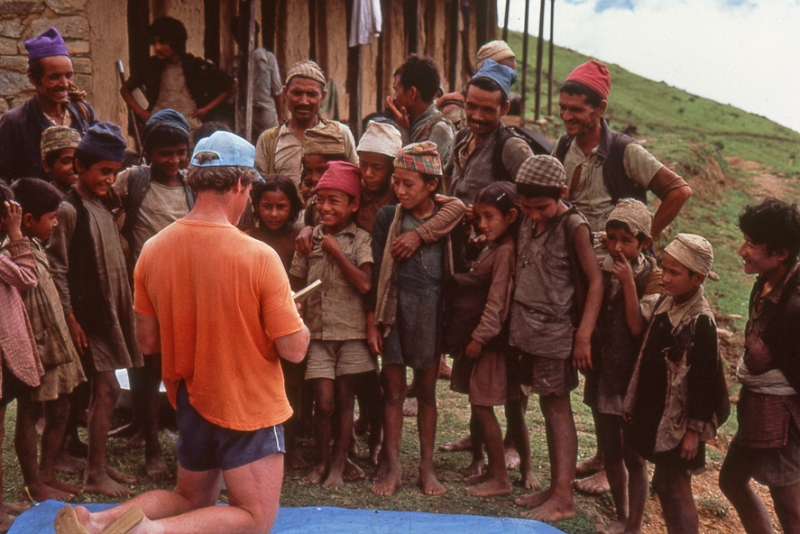

Predictably these diverse entities sought the counsel of the American Alpine Club (AAC), which willingly assumed responsibility for organizing what became the “American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition” (AAME). The AAC assembled an expedition team forthwith, selecting members with view to representing a broad geographic diversity across the USA, and under the leadership of distinguished mountaineer Nicholas (Nick) Clinch. Having worked in the Sentinel Range previously as a geology student under an NSF research grant, I was one of the few active American climbers with prior Antarctic experience. This was key to my making the cut for the 10-man team, as was the case for noted mountaineer and Antarctic geologist Bill Long, who incidentally had been on the 1957 overland traverse mentioned above which made the first sighting of Vinson from the ground.

The diary starts a month before we left the U.S.A., with comments on the protracted ‘off-again, on-again’ machinations of the diverse supporting entities. Notable recurrent themes include

- The almost daily meal descriptions which attest to the food fantasies that haunted us throughout the trip, and

- The sporadic references to my own preoccupation with the west face of Mt. Tyree, best understood in the context of my being an unrepentant Yosemite wall rat at the time.